October 28, 2010

By Tom Hooey

September rut yields the biggest bulls.

By Tom Hooey

Northwest British Columbia moose country is wild and wonderful. With few residents outside its primary cities in the south, moose hunters who come here witness vistas rarely seen by man. |

September is the month for moose, the most majestic deer in the world. I took a trophy bull in the Cassiar Mountains of northwest British Columbia in 2005 while hunting Cassiar Stone Outfitter's 3,000-square-mile wilderness concession. The hunting was difficult, the travel endless and, between sunny days, freezing nights, continuous rain and one nasty blizzard, the weather was erratic. If we had an accident, help might be days away. We communicated with the outside world by satellite phone. No cell phones, no fax, no Internet, no television. Consequently, this was a wonderful trip, the very best kind of bowhunting adventure!

The Bigger They Are

Moose are extraordinarily difficult to hunt, but not because a broadhead has any difficulty dropping a 1,500-pound bull. It does not.

Advertisement

Habitat is the key. The British Columbia (BC) outback is exceedingly remote. Weather, terrain and fatigue -- physical and mental -- are the enemy.

Just getting to camp is challenging. I flew for a day -- several jetliners to Whitehorse, Yukon -- and then drove south to Atlin, BC. From Atlin, I boarded a floatplane into the mountains, landing on a deep, narrow lake and taxiing to a plywood cabin. Two days after I left home, I was ready to hunt, but could only fish because it is illegal to fly and hunt the same day. In consolation, that night we feasted on fresh rainbow trout.

Advertisement

The bowhunting quickly settled into a conventional routine though, crawling out of sleeping bags at 4 a.m., climbing high and glassing lake edges, meadows and willow thickets from first light.

The 10 days I hunted BC -- Sept. 17-27, 2005 -- were the peak of the rut. It was a rare day when we did not see moose. "The willows are eight to 12 feet tall and quite thick, eh," Pete, my Canadian guide, cautioned. "So watch for movement like a fish swirling in the water, eh, and look for the tips of antlers. The bulls have rubbed the velvet off and polished them."

The first rule of hunting Canada or Alaska-Yukon moose is to climb to a good vantage point and glass the surrounding terrain. Because a moose is so dark -- or, conversely, during the rut the tips of its antlers are so white -- one can be easily spotted in a meadow or moving through the willows. |

We saw plenty of moose. Day one. Day two. Day three. A cow, a calf, a cow and calf, then an immature bull. We stalked the swampy moose meadows and called, hoping to be mistaken for a needy female or a challenging bull. At lunch, we fished both sides of the Continental Divide: rainbow trout to the west, northern pike and lake trout to the east.

Each night, we stumbled into our sleeping bags wet and weary. Between violent rains, climbing to overlooks, hiking trackless miles and, even more grueling, moving quietly through dark spruce forests filled with blow-downs, moose hunting proved more exhausting than I expected.

Grizzly Moment

On day four, we encountered a grizzly. As we spread damp jackets in the sun and ate a late fish sandwich, a silvertip emerged from the forest several hundred yards away and turned toward us. Caught off guard, we prepared to retreat.

British Columbia prohibits flying and hunting the same day. Fortunately, the fishing is superb! |

The bear stood and sniffed the wind. I am six feet, four inches tall, and the top of my head would not have reached its shoulders. Then, probably catching our scent, the griz turned and ran. I have never seen an animal move faster; certainly no half-ton beast. It covered hundreds of yards in seconds and vanished into the trees.

Our grizzly moment was brief but emotionally draining, and we collapsed on the rocks. It would have felt good to relax in the warm sun. But with only a few hours of light remaining, we dutifully hiked uphill to a granite outcrop. We moved cautiously, because out there somewhere was a large bear that was quite possibly very hungry. We assumed the worst.

Panting from exertion, attentive to a storm building behind the mountains, we spotted moose: cow, calf and a keeper bull. What we did not see however, the great bear, concerned us most.

"There's less than an hour of light, eh," Pete said. "Let's give it a go tomorrow."

And so, the moment I had never prepared for arrived, a disagreement with my guide.

"No," I decided, "we're going for it."

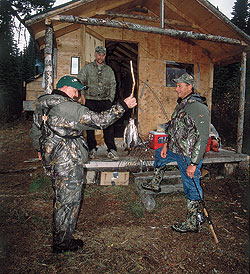

Once a 1,200-1,500-pound bull moose is down, the joy of triumph morphs into the determination needed to process the meat and prepare the cape. Here, Hooey inspects his bull's hide to locate the broadhead's entry and exit holes. |

Pete shrugged. Together, we ran down and into the darkening forest. High stepping over blow-downs and blundering through the half tones of early evening, we dropped our packs and scrambled forward almost a mile.

The best path led left, in the direction of the disappearing grizzly. As we edged out of the forest and into the verge of the tall-grass meadow, the cow spotted us, turned and ran with her calf. The bull held its ground, even advancing toward us across the boggy glade.

Pyrrhic Victory

Pete and I dropped into the muck, crawled forward and peered through the grass.

Incredibly, the bull had not identified us, or else had decided the movement signified another moose. It snorted aggressively, hoofed a rut pit and peed into it.

With barely 30 minutes of light remaining, clouds began boiling over the mountains. Picturesque and magnificent, the moose sto

od with its back to the storm, beat the willows with its antlers and moved steadily toward us, stiff-legged and menacing. It tipped its rack to the left and then to the right, and continued this rocking motion until it halted, just outside bow range.

Tim Hooey proudly poses with his Pope and Young Canada moose from British Columbia. The bull's antlers green scored 193€‰5„8 inches. |

We were not the reason for the bull's aggressiveness, though. Unnoticed, another bull, smaller and probably younger, had stepped out of the willows. Immediately, the bulls squared off, rocking their enormous antlers from side to side, circling, grunting and roaring. The smaller newcomer was not intimidated. It snorted aggressively, faked a charge and, quite unexpectedly, the bigger bull turned and ran.

Pete had crawled behind me, and the moment the big bull backed away, he made a cow call -- a low, rasping rattle deep in his throat. As the younger bull turned toward us, I rolled over in the marsh grass and nocked an arrow.

Thirty yards away, the bull spotted us and halted. It flapped its lips and snorted like a horse. In the crossing gusts from the looming storm, it could not smell us, and so it stared, wondering about the small creatures cowering beneath it.

Finally, youthful impatience led to a mistake. The bull edged left to move around and that gave me a 27-yard shot. I released when the bull was almost broadside, fearing that at any moment, it would smell us and run.

I had no reason to fear, though. The bull did not outrun the arrow. Instead, the broadhead clipped a lung and the arrow sped completely through.

The bull spun and disappeared as quickly as I imagined it might. I thought, "Oh, my God!" and adrenaline shook me like a retriever climbing out of a lake.

"Great shot!" Pete shouted. "You hit him hard, eh."

"I don't think I got both lungs," I said. "Its left leg might have been back."

"Well, let's leave it until tomorrow, eh," the guide said, pulling a flashlight out of his pocket. "There's a bear out here somewhere."

"That's what I'm afraid of," I said, thinking more of the moose than my own skin.

I worried all night. But the next morning, we found the arrow, a massive blood trail hardly diminished by the rain and, just 50 yards from where it had been hit, the bull itself.

That day, the seventh of my 10-day hunt, was wonderful €¦ and miserable. We green scored the bull at 193€‰5„8 and measured the antler spread at 55 inches. As we carried the antlers, cape and meat to the shore -- trip after endless trip over the blow-downs and through the bog -- the temperature fell and it began to snow.