October 28, 2010

A Simple Caribou Hunt Becomes A Journey Into A Proud Past

One of two bull caribou the author was able to secure on his trip to northern Quebec. The trip started with a trickle of animals and ended with a flourish. Having filled his tags in four days, the author had time for fishing and exploring, but the best caribou began to appear on about day five of this six-day hunt. |

In geologic time, Nunavik is a land of newness, because little can be old in a place that until recently was covered with ice. The people are new, the caribou are new, even the rocks are new, laid on top of the land by the melting, moving glaciers. Looking across the clean and barren landscape creates illusions in scale. The country from horizon to horizon could be a rocky scarp as big as your backyard.

Nunavik is more than a rock scarp; it lives and breathes with the life of the tundra, the lichen, the moss, the berry, the fish, the caribou, the wolf and the Inuit — the people. Lying between Hudson Bay and the North Atlantic Ocean and capping the northernmost portion of the vast province of Quebec, Nunavik is a place where natives hunt beluga whale and walrus in the spring, catch char and trout in the summer, trap wolf and fox in the winter and hunt caribou year-round. The simple lives of these northern people have, until recently, changed little for thousands of years. They are the last vestige of primitives on the North American continent, as close as you will come to knowing natives who have only recently stepped into the modern world, who still understand, and in some cases practice, the culture that sustained them here for so long.

Advertisement

I have hunted the caribou of the Northwest Territories, of Manitoba and the lands west of HudsonÂ's Bay, and I have seen the people there, the Denai, almost decimated by the policies of an intrusive government. So when I traveled farther east to this peninsula that looks across to Baffin Island, I expected the same kind of natives, the same kind of disenfranchisement, a culture disconnected from its roots, from the land, the animals and its own traditions, then I met David Angutinquak.

David is the best of the new generation of Inuit, enterprising and forward-thinking yet steeped in the richness of his own culture, and proud of it. I knew from the moment I met him — from the time I first heard his enthusiasm for his land, for the hunt, for fishing and particularly for bowhunting — that I had been matched with the right person.

Advertisement

My primary purpose for visiting Nunavik, of course, was to bowhunt, to take two caribou bulls if possible during this hunt arranged by Sammy Cantafio of Ungava Adventures. David would be my guide. In addition to bowhunting, he wished to spend a good portion of our time exploring the land together, looking for signs of the camps, the hunting grounds and the tools and markers of his people. I felt privileged to accompany him.

READING THE SIGNS

Developing an eye for the arctic is like any other pursuit. At first glance the landscape is a blur, lacking detail or life, and certainly lacking caribou. Then, little by little the land reveals itself, its creases and crannies and its creatures.

David and I spent the first evening trekking to a distant, established caribou crossing. The land yielded willingly to our knee-high boots, and our gait was fueled by the enthusiasm of a fresh hunt. When a small lake of several acres blocked our path we simply forded the shallow water. David led the way and I followed, happy to see the bottom was gravelly and firm, not boot-sucking like the Midwestern sloughs IÂ'd grown up with.

A half-hour into our trek we spotted several caribou bull a mile away, picking their way across the tundra. David guessed the animals might be headed for our crossing, so we pushed on through the moss, scattered rocks, short sedge and caribou trails, hoping to intercept the band. We arrived at a muddy crossing formed between two arms of water and decided to wait out the bulls, but no sooner had we settled in than four cow caribou and two calves made their way past, catching our wind once they had crossed. Our odor — undoubtedly mine in particular, smelling of Montreal, Kujuaaq, airplane fuel and God knows what else — sent the animals fleeing.

As colorful as a sunrise, this Arctic char couldnÂ't resist JayÂ's fly-rod offering. Many of the char in these waters are landlocked, but these brightly colored fish, and some much larger, are ocean-run individuals, powerful swimmers that prefer fast water. |

A short time later, what may have been one of the same cow caribou came straight back through the same crossing. David explained this to me. Â"She is going back to warn the others, the bulls, about the hunters (us). I found his reasoning quaint, and though I doubted its validity, I am not one to totally discount any natural phenomenon. An hour later and long after they should have arrived, we were still waiting for the bulls as darkness settled. Hmm?

HUNTING FOR THE PAST

Because David and his relatives are coastal Inuit, much of the country we were seeing was new to him. He had traveled here overland from the Ungava Bay coast by snow machine but had never seen this country free of the cover of snow. His ancestors, however, had camped and hunted here, making long overland treks in both summer and winter. We were to see the remnants of those camps, those journeys.

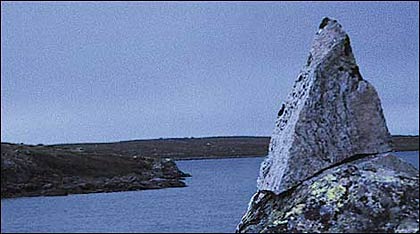

Our first task was to take a caribou bull, but David wanted me to see a place a mile from camp by boat where his ancestors had ambushed caribou. We entered a small bay where David cut the motor and gently guided the boat into a cranny in the shoreline. Above us, set on a smooth-rock ridge, was an obvious cairn, the rock markers used to identify significant locations. Pointed at the top and shaped like an elongated triangle, the single rock at a distance reminded me of a perched falcon with wings folded at its sides. We would see other cairns of this general configuration.

David said the cairn probably marked a fishing spot, where winter travelers could stop and expect to catch fish to feed their dogs. Farther up the bay he pointed to the ridge top where a series of rock structures stood guard. Â"What do they look like?Â" he asked me. Â"People,Â" I replied. Â"That is what they are supposed to look like,Â" he told me. The vertical stones, with their eerie coldness, were set to look like humans, upright and stolid. When the caribou followed the curve of the bay in their travels, they could be herded toward the human-like cairns and funneled to waiting hunters with bows and spears.

Before we could inspect the rock figures, a

small band of caribou appeared on a nearby ridge, all cows and calves, headed our way. David offered that I might shoot a cow on his tag for meat to send home to his family. It would be good practice for a bull, he insisted. One of the cows noticed our movement and came our way to investigate (a strange, often annoying habit that cows frequently engage in).

Crouched behind a rock, I nocked an arrow. When I peeked over the top, the cow was already within range. I rose to clear the boulder, drew and released in one motion, sending an arrow over the top of the animalÂ's back. David was right; it was good practice.

We stopped around noon to catch several lake trout for a shore lunch and shared them over a small fire with DavidÂ's Inuit friend and fellow guide, Jimmy, and his two rifle-hunting clients. The trio had a decent bull caped and loaded into their boat and was looking for another. David and I hunted the remainder of the day with little success, seeing only more cows and calves and a few young bulls.

CAMP COMFORTS

There are many joys to a caribou camp, but the most obvious may be that here in one of the most forsaken places on the planet one always has a warm, dry shelter and hot food to return to. Another delight, particularly for a whitetail hunter from the 4 a.m. school of up-and-at-em, is that caribou do not require rising early. As a matter of fact, there is no real advantage to hunting caribou at the crack of dawn.

Following morning helpings of sausages, buttered toast and eggs, David and I set out on a long boat trip to try to locate the caribou bulls that had eluded us. Along the way we shot upstream through several boulder-strewn rapids, with David generously allowing me to slow our travels by stopping to fish. In the pools, hungry lake trout grabbed my flashing spoons, and in one stretch of fast water I used streamers and my fly rod to fool sea-run Arctic char, so brilliantly colored they looked like flames under the torrent.

We stopped on one otherwise unremarkable shoreline to view the site of an ancient encampment. How David knew this might be here still remains a mystery, but as the trip progressed I became accustomed to his eye for signs of his own people.

What we found were the stones that marked the walls of skin tents, 10- to 30-pound rocks laid out in a rectangular pattern where they had held the edges of the tent against the wind and weather. Two tents had been located here, the largest some 20 feet across, the smaller about half that size. David moved a stone to look at the depth of the moss that surrounded it, his method of dating the peopleÂ's passing. Moss takes decades, even centuries to grow in this harsh land, so a rock imbedded in even a small amount of moss cannot have been placed recently.

Rock cairns like this one marked important fishing or hunting grounds or pathways for the Inuit. This shape was seen repeatedly in separate places. Notice how the large cairn was selected to fit the contour of the rock it rests upon. |

While DavidÂ's sharp eye studied the ground, I surveyed the landscape. Did the inhabitants of this camp meditate on the beauty of this lake, of this tundra, as I was doing now? What were their lives like? Were they well fed and clothed, as we were? Or were they struggling to survive? Did their children play here? Were they called to dinner? No doubt all the emotions of life were played out in a semipermanent camp like this. Love, sadness, happiness, fear. Now, of all those seemingly important events, all that remain are rocks.

CLOSING IN

It was after a short shore lunch that David spotted the bull caribou. The animal was at least two miles away, and it was sheer luck the bull had come up in the glasses because now he had disappeared again behind one of the interminable creases in this landscape. When he reappeared he had a friend with him, another good-sized bull.

David and I immediately launched into a plan. We would proceed as far as possible by water, then use a ridgeline to conceal us as we stalked the beasts.

By the time we traveled and again located the animals, nearly an hour had passed. David believed the bulls were headed for an isthmus in the lake, so we hurried to the crossing, intent on an ambush. DavidÂ's sharp eye soon noted that we werenÂ't alone in appreciating such a spot. Precisely where we planned to ambush the caribou, a pile of moss-covered rocks the size of a beaver house stood guard. The rock pile, David explained, was used as a crib, or storage locker for dead caribou, deterring wolves, yet allowing the Inuit to return in winter and chop off chunks of frozen meat.

We waited near this site, and I was extremely excited about the possibility of killing a caribou in such a traditional place. The caribou, on the other hand, werenÂ't cooperating. More than an hour had passed since the last time we had seen the animals, and they were long overdue. We agreed to sneak to the top of a nearby rise to try to locate the animals, but before we could get there we spotted the bulls bedded only a couple of hundred yards away. Their numbers had grown to three. Once they got up they were sure to head for the nearby crossing.

Another hour passed as we lay in wait, but the caribou never showed. When we looked for them in their beds, they were gone, but they reappeared on a hillside a quarter mile away. We had to move fast. With all the speed we could muster, we made our way to the same ridge the bulls fed upon. They were working our way. As fate would have it, the first two bulls to approach took sudden turns and fled uphill onto an unapproachable ridge. If the third followed, all hope of taking these animals would be lost.

The gods smiled. The third bull continued in our direction, but just as he approached a suitable range, the lead bull spotted us from his position on the ridge. It was now or never, and I would have one move that didnÂ't include ranging my range finder. I guessed the bull at 35 yards and let an arrow fly that struck him low in the chest, a perfect heart shot. He ran a small half circle and went down.

A PERFECT TRIP

Three days later I capped a day of running up and down small mountains, sucking through mud, hiding in rocks, battling a temporary plague of black flies and spooking several good herds of caribou by shooting another good bull. This one had an even prettier cape than the first, and I planned to perhaps combine the rack of one with the cape of another for a great wall mount.

David and I had finished our trip by wearing ourselves out catching and releasing lake trout, and we had the pleasure of locating several more ancient encampments, including one that yielded a primitive soapstone oil lamp that will be entrusted to a museum. I learned that loons are the most promiscuous of animals and that caribou have noses in their feet that help them follow the herd. I cannot wait to return to Quebec to learn more.